There’s a word that keeps popping up in conversations about AI: agency. It’s a kind of well-intentioned marketing gloss—companies, founders, and pundits love to say that AI will “increase human agency.” I certainly want that future. But if you listen closely, what they often mean is something much smaller: AI helps us do more stuff, faster.

The examples usually involve a single human having an increased ability to accomplish some task: write code without coding; make slides without designing; generate text, images, or videos on command. Often the examples rise to a higher level: a person’s ability to learn more or create a business faster and at lower cost. This is all valuable (except when it’s hallucinated nonsense), and there are many words to describe what is being increased: capability, efficiency, and skills to name a few.

But agency is not one of them. That’s because agency means much more than increased productivity.

What Agency Really Means

Allow me to make two quick definitional acknowledgements.

First, there’s an entirely different conversation about “agents” that refers to giving AI systems more autonomy and ability to more independently take action on behalf of a human. I’m not here to write about that kind of “agentic AI.” I’m here to dig into the agency of us humans.

Second, normal people don’t talk about “agency” when it comes to ourselves. Philosophers, economists, sociologists, psychologists, and people who do professional work in diversity, equity, and inclusion do. But I doubt you’ve had many normal human interactions in which “agency” came up that wasn’t in reference to a government department or office. I’m using the term here because influential voices in the world of AI have latched onto it. So, “human agency” it is!

It’s worth taking a wider view of this term. Here, the Wikipedia page on the philosophical meanings of agency is useful. I also found this Perplexity search result to be quite useful in helping distill some key elements of agency.

My takeaway from all this, and my own sensing, is that agency involves at least three key elements:

The capacity to make intentional choices

The power to act on those choices

The ability to shape your environment and future

These definitions hold not just in the realm of tech but in life, both individual and collective.

In the context of AI, human agency is not just being able to type a prompt and watch something appear. It’s being able to decide what really matters, and having the power to influence how things unfold.

For months, I’ve struggled to articulate this. Back in April 2025, I was reading Reid Hoffman’s book, Superagency, in preparation for my interview with him for Life With Machines. My wife and show co-creator Elizabeth felt there was something lacking in his definition, but she wasn’t able to fully articulate that thing at the time. Our entire production team felt it, but we couldn’t clearly name it either.

That changed last week. As Elizabeth and I dined near Place de la Bastille in Paris—we’ve been here for my birthday—perhaps aided by proximity to the constant state of revolutionary energy in this city or just the zero-tariff access to good wine, we had a mental breakthrough: agency isn’t just acquiring skills. True agency requires power. You can have all the skills in the world, but if you don’t have the power to use them to shape outcomes—political, economic, social—then you don’t really have agency.

Reid Hoffman and the Agency Gap

When I talked with Reid, he described agency as “a sense of capability, presence, and meaning in the world where I can shape significant things that matter to me.” That’s a solid start, and you should check out the few minutes of our exchange here for even more context, and my post-interview newsletter.

But even Reid, who is distinct from many in Silicon Valley in his continued belief in democracy, leans heavily on the individual side which tends toward what you can do faster, what you can learn quicker, what apps you can vibe-code into existence. His definition doesn’t mention power, governance, or shared decision-making…the things that make agency real.

As I continue listening to the AI discourse, what’s often missing is the part of agency that deals in power and choice and usually requires collective applications like:

Who gets to decide how AI is deployed?

Who governs the platforms and sets the rules?

Who shares in the power AI generates?

Without that layer, we’re just getting shinier tools handed down after the real decisions have already been made.

And Now, for an Advanced Visual Aid

So far I’ve used a lot of words, but I invested heavily in a graphical design element to communicate what I think is going on with this word agency.

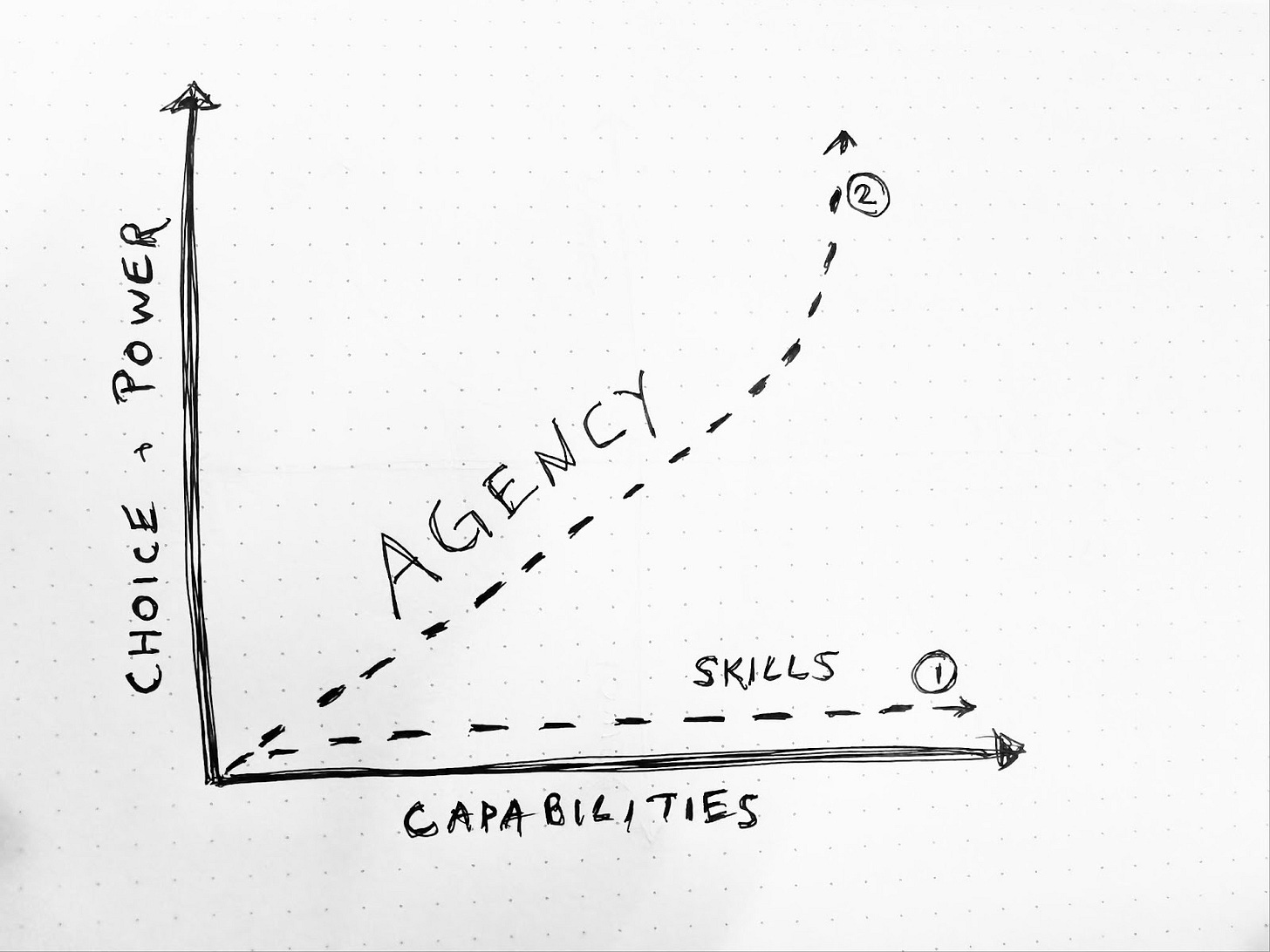

In the first image, the X-axis represents capabilities, and the Y-Axis represents choice and power. Most of the conversation about human agency is along the Line #1, just increasing capabilities horizontally with no real increase in power vertically. The path of increased human agency would look more like Line #2, moving to the right and also up.

TRUE AGENCY INVOLVES CAPABILITIES + CHOICE + POWER

This is literally a flat existence. We get more skills and can do more but without accompanying power, we can also be used more, to work, to consume, to produce in the interest of a system that has little to no interest in our well-being and certainly no interest in actually increasing our power.

This is productivity-obsessed AI. It’s LLM-based hustle and grind culture. Hooray, we can burn out faster.

But if we take the second path, we get lifted (Thanks, John Legend!). In this scenario, we individually and collectively decide how we want to use these new capabilities to shape our world and environment. This looks like groups of people using technology to collectively decide if and how to use AI, as I’ve recently learned Gradient Learning helps classrooms decide how to integrate AI into school work (teaser: more on that soon!).

True human agency would thrive in a world where we have meaningful choices among which AI frontier models to use, or whether to use LLM-based systems at all. We could be empowered to make informed choices by having transparent access to the energy and climate costs of various AI systems. Employers would involve employees in the design and deployment of AI systems because they would take seriously the idea of “nothing about us without us,” and we wouldn’t see people hiding behind AI as a justification to lay people off. We would see thriving data cooperatives and localized development and control of models. We might even upgrade our democracy to be ready for this AI-infused future with concepts like those of Audrey Tang and

(check out on this).There are many more possibilities to imagine and worlds to create when we take the idea of human agency widely and seriously.

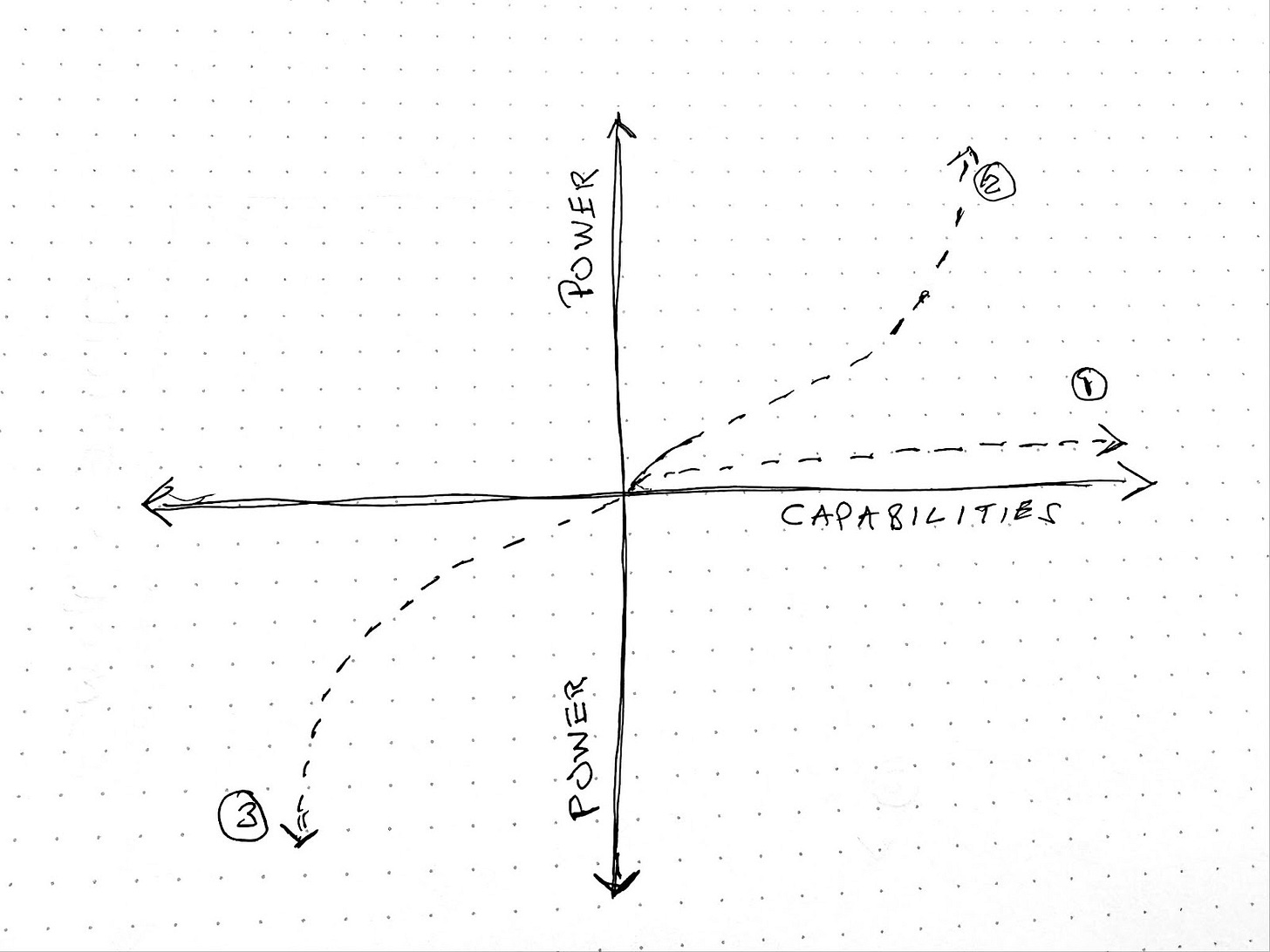

But there’s one more missing part of the human agency conversation I’ll point out before wrapping this up. Most conversations assume that humanity is at minimum moving to the right on the X-axis, increasing capabilities (Line #1 below), and it’s just a matter of how far. I’ve tried here to introduce vertical movement to represent the need to increase power as well (Line #2). But even I have been assuming a degree of positive motion, and there’s also a very real possibility of sliding backwards, down and to the left, Line #3 in the advanced graphical image below.

WE MIGHT ALSO LOSE HUMAN AGENCY BY EMBRACING AI THE WRONG WAY

I’ve talked with enough coders to know that vibe-coding, for example, risks reducing a person’s coding skills, and I recently chronicled my own concerns about my Oura ring and the risks of outsourcing my very knowledge of self. MIT released a recent study hinting at possible reduction of brain activity and cognitive function with AI use. And the U.S. public has an overwhelmingly negative expectation of the impact of AI usage on human capabilities. Or you could just look at the real-time loss of skill on display at Meta Connect where the human asking “What do I do first?” is a literal predictor of our most commonly uttered phrase in a future where we outsource completely to completely unreliable systems

More worrying to me is the possibility that we will become addicted to tools defined and controlled by narrow interests whose primary goal is seeking profits, not widely improving collective well-being. That kind of dependence on central authority is the very opposite of agency. And just because Zuck has made it easy to mock him recently, I ask, is this your king??

Life with machines shouldn’t mean life under machines—or under the corporations that control them.

Your Turn

When you hear AI pitched as “increasing your agency,” ask yourself:

Do I just have new capabilities?

Or do I have new power?

And… Who really gets to choose?

That’s the real agency test.

Reply and let us know: Where have you seen real agency—capability plus power—at work with AI? And where do you see us just confusing productivity with freedom?

Peace,

Baratunde

Thanks to Associate Producer Layne Deyling Cherland for editorial and production support and to my executive assistant Mae Abellanosa.

I don't remember where I heard this line of reasoning, but it was a Matrix-like point of view: "In the future there will be those who control the machines, and those who are controlled by the machines, and I intend to be in the first group!" I do very much worry about people who are already slipping southwest of the center of your super-high-tech data viz: those in the "3" category. We've often talked about the loss of agency by peoples' value as producers being converted into value as consumers, but the AI-assisted grind that magnifies skills but diminishes impact is a concern.

Really lovely point here, that power is central to agency at every juncture in the creation and evolution of the technology. I wonder what would be different if we afforded each other agency not just in deploying LLMs, but in evolving the design of the interactions we have with them